Originally published by The 19th

Ten days before the release of her highly anticipated album “Cowboy Carter,” Beyoncé shared on Instagram that the project began as a result of feeling unwelcome in the country music space.

“Because of that experience, I did a deeper dive into the history of Country music and studied our rich musical archive,” her post said. “The criticisms I faced when I first entered this genre forced me to propel past the limitations that were put on me.”

In her message, she appears to reference a 2016 performance of her song “Daddy Lessons” alongside The Chicks at the Country Music Awards. The collaboration was a standout moment in the show, with Beyoncé fully leaning into a sound many of her fans never knew they needed from her.

But with the praise also came backlash. Comments flooding social media at the time ranged from standard celebrity criticism to blatant racism.

“That’s right folks. Beyoncé performed at the CMAs last night & is on a mission to take country music away from us, hardworking white people!” said one online comment reported by news outlets.

This moment in music history, while high profile, is not surprising — particularly for Black fans who have been navigating this dynamic for years. Though country music as an art form developed from the sounds of Black musicians, the commercial country music industry was explicitly created to court rural, White listeners in the 1920s. More than 100 years later, its connection to Black audiences remains fractured. There are, however, plenty of Black people who live in rural communities, participate in rodeos and — yes — listen to country music.

In interviews with The 19th, a dozen Black fans of country discussed reconciling their love for the music with its racist, misogynistic past, as well as the pervasive image of White men who continue to dominate the mainstream industry. They are hopeful that Beyoncé and “Cowboy Carter,” released Friday, will help elevate Black country artists and serve as a bridge for more Black people to feel comfortable listening.

“I think that Beyoncé fans have such a huge opportunity here to really come in and help boost some of these artists,” said Holly G, founder of the Black Opry, a community for Black artists and fans that produces country and Americana shows around the United States. “I totally understand why Black people would not want to give country music a chance given the way that the industry has treated them, but I think they would really, really enjoy the music.”

Before the creation of spaces like the Black Opry, being a Black country lover was often a lonely experience. Several Black fans told The 19th they did not know many other Black people who liked country music, and they also encountered confusion or dismissiveness from some White fans.

Growing up going to country concerts, Stephanie Jacques used to play a game counting the other Black people in attendance. For the most part she never felt unsafe: Jacques is a biracial woman who was raised by a Southern grandma in a White suburban California town, so she had a certain level of ease in White spaces, she said.

Still, there were clear indicators that Black people were not welcome at country shows. She recalled seeing Confederate flags and being called the N-word at a concert in Virginia.

Jacques went on to sing professionally herself, but it took years for her to open up to the idea of singing country rather than strictly soul and R&B.

“I think it was the lack of representation, and not seeing other women who looked like me,” Jacques said. “It actually took till about eight years ago that I decided, ‘No, country is the genre for me.’ I moved to Nashville seven years ago.”

Tara Nelson has her own roller coaster relationship with country culture. She grew up enjoying country music and attended a small, predominantly White university in Washington state. Despite encountering people there who had never met a Black person before, Nelson made friends: She and her college group would frequently go line dancing at country bars in the late ’90s.

Eventually, the discomfort Nelson felt in those venues became impossible to ignore. The curious stares or repetitive questions that insisted on probing why she liked country music took a toll. The environment made Nelson feel like she did not belong.

“It really kind of hit me that maybe country music was not something that I should be listening to, or enjoying — or at least that I should not say out loud that I listened to it,” she said. “I thought, ‘Maybe I need to do this in secret so that no one takes it away from me.’”

Nelson stopped going line dancing. She packed away her Garth Brooks and Reba McEntire CDs. Over time, she stopped listening to country music entirely, which lasted until recent years.

“It’s really too bad that I did that to myself, because I’ve missed out on finding Black country artists,” Nelson said.

Over nearly two centuries, the landscape of country music was intentionally curated. The sounds of early country before the official “country” label are rooted in singing styles and instruments that were almost exclusively associated with enslaved Black people in the early 1800s.

Minstrel shows of the 1830s marked a turning point. White actors darkened their skin with makeup for blackface performances that sought to mimic the music and dances of Black slaves. These shows were one of the most popular sources of entertainment for White audiences and laid the groundwork for the commercial country music recording industry that began in 1922.

At the beginning, commercial country was designated under the marketing category of “hillbilly” and “old time” music that was restricted to White artists and aimed at White rural audiences, said Amanda Martínez, a historian and postdoctoral fellow at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Blues, jazz and gospel music were genres marketed as “race records” meant for Black consumers.

“If you think about the popular music marketplace, each type of music is for a certain type of person. It’s always been defined by the consumer,” Martínez said. “The country music audience has evolved over time — it’s mostly the class politics that have changed over the last 100 years. The industry has always identified its place in the market as for White people.”

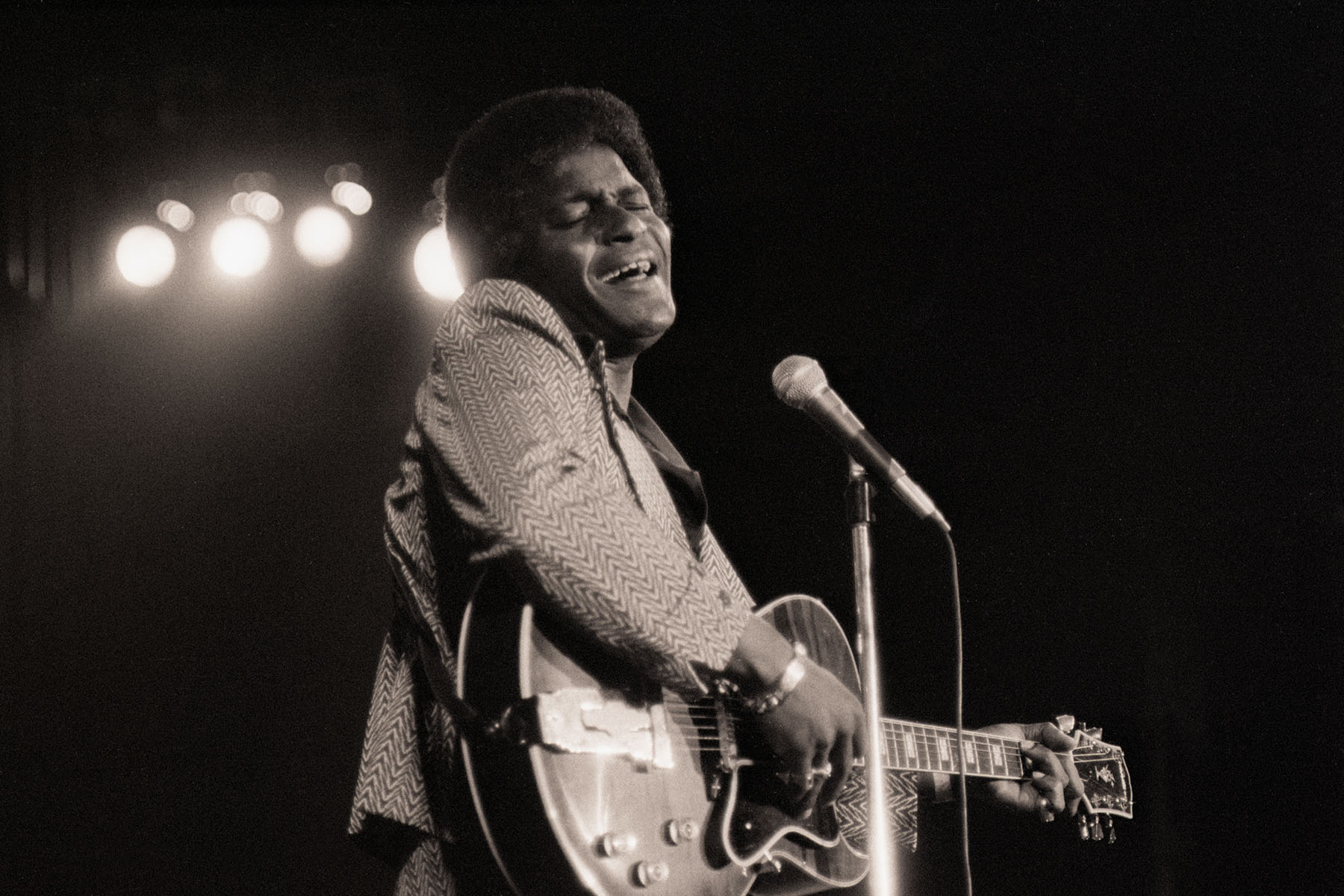

Charley Pride’s commercial recording success in the 1960s was a pivotal point that opened up possibilities to Black country singers. After Pride’s ascent, singer Linda Martell pivoted from R&B to country and became the first commercially successful Black woman in country music.

The 1970s offered a glimmer of hope for Black women in country, as singers including Martell, Ruby Falls, Barbara Cooper, Lenora Ross and Virginia Kirby experienced some popularity, Martínez said. By the end of the decade, however, the door to Black singers had closed again. A growing “Redneck chic” trend that glamorized the image of a stereotypical White Southerner took hold of American society, Martínez wrote in a 2020 article. It also seeped into national politics. Ronald Reagan, the Hollywood cowboy-turned-politician, pushed to cement country music’s tie to White conservative identity.

“One of the ways we have constructed race in America in the 20th century is to divide musical audiences,” said Alice Randall, a songwriter, Vanderbilt University humanities professor and author of the upcoming book “My Black Country: A Journey Through Country Music’s Black Past, Present, and Future.”

“One of the ways I want to deconstruct racial bias in America is to take a deeper look at these divisions, how they’re constructed and why they’re constructed,” she continued.

Despite these barriers, Randall and other Black artists still found ways to break through. When Randall moved to Nashville to pursue music in the 1980s, she struggled with feeling isolated as one of a few, if any, Black people in the spaces around her. Throughout that time, Randall said she channeled the strength of those who came before her — her “first family of Black Country.” In 1994, she was the first Black woman to write a number-one country hit with the song “Xxx’s and Ooo’s (An American Girl)” sung by Trisha Yearwood.

Black women like Randall, Dona Mason, Etta Baker, Rissi Palmer, Rhiannon Giddens and Mickey Guyton have paved the road to Beyoncé’s “Cowboy Carter,” but the reality of country music’s dark history lingers with modest change.

One data analysis by Ottawa University professor Jada Watson found that in 2022, women artists received just 11 percent of all airplay on the 156 country stations that report their data to Mediabase, a music industry service that monitors radio station airplay in 180 markets throughout the United States and Canada.

A separate report by Watson found that between 2002 and 2007, artists of color represented an average of 0.3 percent of the airplay on country radio. That representation has increased slightly: By 2020, they received 4.8 percent of the annual airplay.

For most Black country fans who spoke with The 19th, this extensive history clearly captures why the genre remains disconnected from broader Black audiences and why problematic criticism of Black artists persists.

Black artists — particularly those who mix country elements with blues, soul or hip-hop — face accusations that they do not represent “authentic” country music. When Lil Nas X, a Black queer performer, released his debut single “Old Town Road” in 2018, it gained viral popularity and praise for its blend of country and trap music. But country radio delayed airplay of the song and it was removed from the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart for allegedly not having enough country elements.

Authenticity conversations today have become another tool to police what groups are allowed to participate in country culture, said Sophia Fifner, a country music fan and Ohio resident.

There’s a lot to be hopeful about when it comes to Beyoncé’s album: her meticulous attention to music history will be educational, and her work is already forcing conversations about the industry’s roots. As a Black woman from Texas, Beyoncé has just as much right as anyone else to claim country music as her own, said Nicole Blanton, a country fan who is also a Texas native.

But this moment surrounding the “Cowboy Carter” release is much bigger than one singer. Fans told The 19th they do not expect the stubborn country music machine to transform any time soon. But they see promise in the people working to create their own avenues for community and representation.

“There are so many of us, and we’ve been here,” said Jacques, the Nashville-based singer. “There are so many artists that are doing country music and deserve so much attention, because they are going to do the work even after Beyoncé is gone. Beyoncé shined a light, and I hope we can keep that light.”